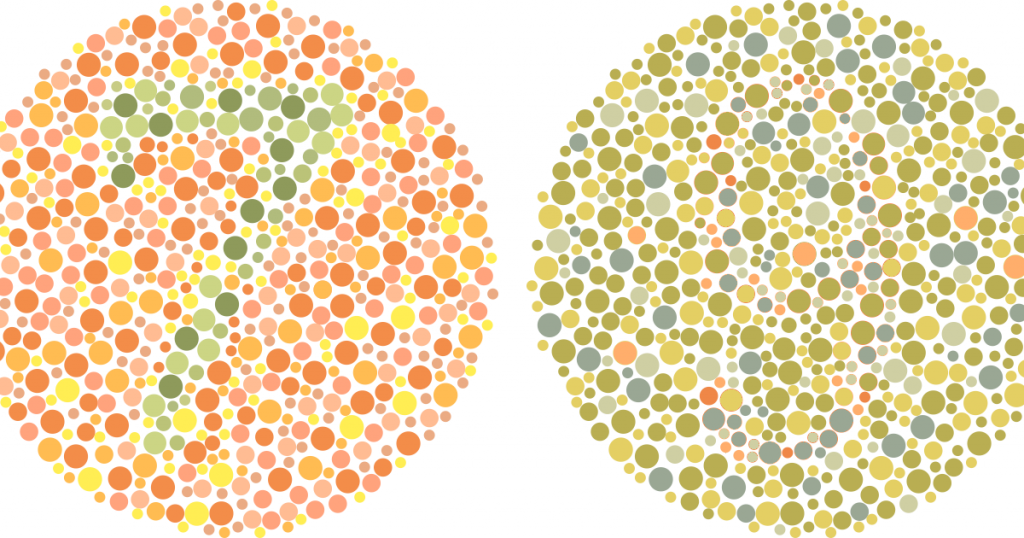

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you’ll probably know that I’m not entirely normal. No, not for that reason. Or that one. No – I suffer from Daltonism aka Deuteranopia. Don’t worry, it’s not serious. As you’ve probably guessed given the title of this post and the images above, those are just fancy words for colour blindness. In fact, for a specific form of colour blindness that, according to this test at least, means that greens, yellows, oranges, reds, and browns may appear similar, especially in low light, and which can also make it difficult to tell the difference between blues and purples, or pinks and greys.

If you want to know about exactly what causes that, then I’m sure you can Google plenty of information. What I want to tell you about is how that affects me in escape rooms. To give some context, colour blindness has almost no effect on my everyday life. Yes, I can tell that the grass is green, that your car is red and that oranges are orange (at least, by my definition of orange).

In fact, the biggest impact it’s had on my life was as a child, when I was presented with tests, like the ones above, and the person giving me the test was convinced I was being deliberately obtuse because I got every one of them “wrong”. Over time, I’ve learned that, if I really, really concentrate and look carefully, I can just about follow the path of the image on the left and work out that it’s displaying a 7 (fingers crossed I’ve got that right). I’d have no hope on the right-hand one. And I guess neither would you, because I deliberately edited it to swap the colours over just to make you know how it feels. I hope it wasn’t too frustrating.

I say that’s the biggest impact it’s had on my life, but that was only until I found out about escape rooms. In escape rooms, colour matters. Ridiculously often. Sometimes in quite important games. Don’t worry; I’m not here to tell you not to put colours into your escape rooms. Colour blindness affects something like 10% of the male population and an even smaller proportion of women. The effect is fairly minor and really doesn’t exclude sufferers from very much, so I don’t think it’s necessary to remove all colour puzzles – that would make life, quite literally, dull. Instead, I’m asking you to think about how you handle colours in games.

There are four things that I really struggle with when it comes to colour: similar shades, low light levels, seeing the colour for a short duration or only seeing a small area so… let’s talk about each of them in turn and see what options there are that might help the colour blind.

Similar shades

You and I probably have a very different idea of what “similar shades” means. For example, I find many yellows and oranges to be very similar in shade. If you want to make me differentiate between two colours, please don’t use yellow and orange. Similarly with the other colour combinations mentioned above. Try to choose ones that are as dissimilar as possible. Black, white, bright red, navy blue, yellow, cornflower blue, bright green. Once you start getting past that set, it rapidly starts going downhill. And yes, I know that I said red and green. I know that those are colours traditionally seen as being difficult to differentiate but, if you choose good bright shades, I think it generally works out OK. For me. I don’t know about the other colour blind people in the world.

Another option is to allow me to move the colours. If I can compare a colour easily to another version, then I’m much more likely to be able to solve your puzzle. I’ve seen this accomplished in two ways: In one, the colours are put onto another object with a definition of what they are. In the right room, that can work very well. The other option is to allow you to physically move the object next to the thing that allows you to decode it or vice versa. That can work well in some rooms but obviously may be implausible in others, for example because it ruins the communication aspect of the puzzle.

Low light levels

How good are you at telling the difference between colours when I turn the lights out? Not very good? Well, that’s kind of how I feel in low light. Now, all sorts of things can be said about avoiding low light in an escape room, but I’m concentrating on the colour aspect. Your eye detects colour using cones. Cones don’t function very well in low light. My eye has fewer/less sensitive cones (possibly just of a particular type). It’s not hard, therefore, to imagine that my eyes are going to struggle recognising colours in low light more than yours.

While we’re on the subject, it’s worth thinking about what colour of ambient lighting you use. If you use bright yellow light and want me to distinguish between greens and blues, you’re going to be disappointed. Make sure you test the colour differentiation with the same lighting as you’ll have in the game. It’s hard to believe how many games leave puzzles virtually unsolvable using the lights in the room, even for non-colour blind people. If you really don’t want to improve the main lighting, then provide a portable white LED light source which gives the same result without changing the whole room.

Short durations

You know how I said that, if I’m really careful, I can decode the colour blindness tests? Well, that’s because, if I take my time, I can start to see the differences between colours. If you reduce the time I can do that for, say by flashing an LED on and off, then I’m going to really struggle. Where possible, give me longer to decode the colour and I’m less likely to have an issue.

Small areas

Similar to the above – the less area I have, the harder it is for me to focus my attention on to it and discern the colour. Ideally give me a swatch of colour that’s at least a couple of centimetres across when held at arm’s length. The further away, the bigger it needs to be.

What else?

There are other things you can think about when designing games. If a puzzle involves colours, you can ask the players before they go in if there are any issues on that front and be particularly helpful at that stage in the game if they hit problems.

If it’s a split room, you should think carefully about which side requires more colour skill and, if they both do, consider splitting the team to give each half a member with better colour vision. That’s not always possible, but I’m reminded of a game I played where I was put on my own and then told to describe pairs of colours to my teammates. Needless to say, it went badly.

Try to keep the number of colours low – do you really need to use 300 colour shades? (One venue I played felt that they did.) Generally, I’d say you can get to around seven different colours without hurting colour blind people much, and that’s likely to be enough to make brute-forcing a solution unappealing.

If all else fails, add a second mechanism to the puzzle – maybe a pattern, texture or a symbol. Ideally, something that’s a little bit more difficult for normal people than using the raw colour. Those lucky people with perfect colour vision can still play the game just fine, and the others can fall back on the slightly more difficult option and still have a puzzle they can tackle. In fact, I recently found out someone has invented colour symbols to help with this sort of issue.

Having said all that, this really isn’t a new field. Yes, escape rooms are reasonably new, and it seems like talking about colour blindness in them is significantly newer, but usability and colour blindness have been around for ages. Google “colour blindness design” and you’ll find research papers, government guidelines and a host of other advice that, while not specifically geared towards the escape industry, will probably be of interest.

Finally, thanks for reading this far. Whether you end up doing something about it or not, the fact that you’re thinking about the issue is a good step in itself.

Permalink